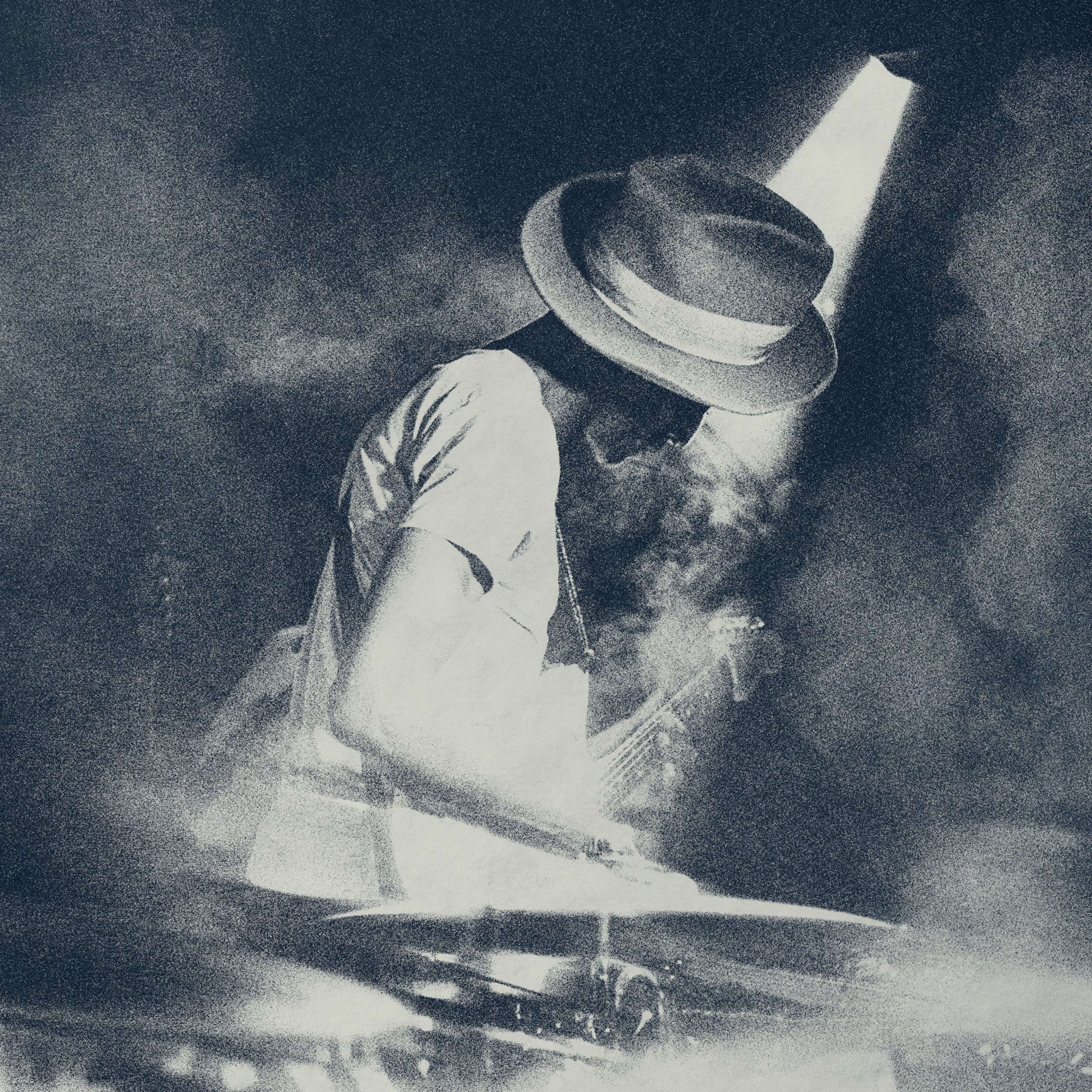

KEZIAH JONES

ALIVE AND KICKING

NEW ALBUM

But Who (Really) Is Keziah Jones?

A committed musician who has never shied away from embracing pop, Keziah Jones stays true to his Nigerian roots while roaming the world freely. He’s the inventor of a major genre – blufunk – yet constantly ready to reinvent himself. A multidisciplinary artist without limits, timeless in his appeal… We’ll never finish discovering the reserved and inspiring Olufemi Sanyaolu, a.k.a. Mister Jones.

Music has always been part of Keziah Jones’ life. He recalls his childhood in Lagos, Nigeria, where the soundtrack ranged from the traditional choirs his father listened to, to his sisters’ records – Michael Jackson, Teddy Pendergrass, Sly Stone… Sundays were the most joyful, especially for the kids who, like him, chose not to accompany their devout Christian mother to church. The stereo was cranked up, a mixed playlist blared through the house, and there was even a small glass of liquor to go around. For young Keziah, music already embodied joy, sharing, and freedom.

But this passion wasn’t confined to the walls of his home. The 1970s, when young Olufemi grew up, were filled with the rhythms broadcasted on radio and television, a consequence of Nigeria’s 1960 independence. This era culminated in a local cultural explosion, which would intensify even further in response to the economic crisis of the 80s, with highlights like the iconic FESTAC of 1977. This international festival, dedicated to promoting all African art forms, left an indelible mark on Keziah and his generation, not just for its radiance but also due to the protest musician Fela Kuti. Though Kuti boycotted the event, he made waves by organizing free concerts nearby that garnered equal, if not more, attention.

In Fela’s Footsteps

The creator of Afrobeat, an iconic blend of jazz, funk, and West African rhythms, Fela Kuti has always been a guiding figure for Keziah. « We come from the same place, and as a child, I passed his house every day on my way to school. I grew up hearing about him constantly and have always admired his music, his courage, and his unwavering commitment to his country, no matter the cost. He remains a model, an inspiration. »

This admiration eventually led to a memorable meeting. In 1997, already an established artist, Keziah pretended to be a journalist to request an interview with Fela, who was gravely ill and hadn’t spoken to the press in a long time. Did Fela see through the ruse? Likely. But he accepted, meeting the young man from the neighbourhood who shared his son’s name, Olufemi (the future Femi Kuti). Their conversation lasted three hours, portions of which were published in magazines. « Fela was very generous. We talked about so many things, and we laughed a lot. He had a great sense of humour, which people often overlook today. If the public got a glimpse of that conversation, they couldn’t truly understand it without hearing the whole thing. That’s why I made several copies of the original recording and gave them to musicians I met along the way, like Beck or Jimmy Cliff. » A fitting conclusion for an encounter that began in 1977, as young Keziah unknowingly prepared to follow in his idol’s footsteps.

London Calling

« Nigeria’s independence still held little significance in people’s minds. After decades of British colonization, England was still seen as the ultimate destination by the older generation, a mindset the youth struggled to understand. My father wanted me to follow in his footsteps and become an engineer. London was supposed to steer me in that direction, but the city only solidified my passion for music. » In his English school, young Olufemi received a well-rounded education, from mathematics to history, and – to his joy – was given the chance to learn an instrument: the clarinet. Meanwhile, his older brother was given a guitar he could hardly play, and it was by trying to help him that Keziah found his own talent.

Encouraged by a Nigerian classmate, he began playing piano and composing songs when he was only ten years old, closely supported by his teachers. But it was years later, as he ventured into London’s folk clubs, that he dared to consider an artistic career. « I was the youngest and the only Black musician, but the other performers welcomed me warmly. I started there, but my style truly developed on the streets. I had to play very loudly to be heard, which shaped my approach to the guitar. » Eventually, his father gave him two years to make his mark before he would be expected to attend university. At eighteen, Keziah felt an urgency to refine his style, which crystallised during a pivotal visit to a record store. “If the best jazz, blues, funk, or world music records were tucked away in the back of the store, it was pop that held pride of place, even though it clearly drew inspiration from those other styles. I was absolutely determined not to end up in the shadows, and I quickly understood what I needed to do.”

The Blufunk Revelation

« I wanted to experiment, to explore the world fully, to open my mind and heart, pour my feelings into my songs, and reach as many people as possible without betraying my roots. I had to find the right path. » From this realisation came the need to sing in English and to adopt a new name that would resonate widely, yet authentically. Thus, he chose « Jones » and later « Keziah » an uncommon Biblical name. Over time, he crafted a new musical genre, « blufunk, » a modern African sound in a pop format and, most importantly, a « universal form of communication. »

After this lengthy period of introspection in his adopted city of London, the artist felt ready to set out elsewhere. Paris called to him as it remained inseparably linked to global icons like Miles Davis in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. His discovery of the city, however, exceeded all his expectations, and almost in astonishment, he encountered an audience far more receptive to his musical explorations than his British listeners had been. This newfound reception gave him the confidence to spread his wings across the French capital, armed with his guitar, hat, and emerging « blufunk. »

Then, the legend—which, for once, holds true—took over. It was at a café terrace near Beaubourg that Keziah’s life changed course when composer Philippe Cohen Solal, the future creative force behind Gotan Project, discovered him and invited him to record his first demos. A modest miracle in his eyes, especially as his father’s ultimatum from two years prior was just about to expire.

A Well-Spent Career

Following his promising debut came six essential studio albums, blending joy with genuine engagement. From Blufunk is a Fact! to Captain Rugged, which delves into Nigeria’s darker side, to Black Orpheus, inspired by Marcel Camus’ Orfeu Negro.

But Keziah has often taken breaks, believing that « making music doesn’t always have to be tied to the music business. » Now, at the end of 2024, he returns with Alive and Kicking, recorded in live conditions in Lagos at Femi Kuti’s studios, featuring covers, new songs, and his biggest hits reimagined. The inventor of blufunk envisioned this album as a thread running through his career – a sort of « recap of past episodes » – released just before he unveils a new record he describes as more experimental, with a strong focus on guitar work. It’s no surprise, then, to find a cover of The Police here, a nod to his formative London years, or a Pass the Joint rendition borrowed from Rick James. While fans will be thrilled to hear his hit “Rhythm is Love” in a new acoustic version, introduced with a jubilant « Paris, c’est moi! », they’ll be equally captivated by his latest love gem, “Melissa”, accompanied by a simple, sunlit music video.

The Alignment of Parallels

As Keziah Jones himself admits, until now he has rarely revealed himself outside of his music. It’s a matter of character, not a rejection of openness. Thus, with the release of his new album, he has chosen to share a bit more of his personal life through a 15-minute documentary created by his friend, Finnish journalist Steve Borth. In short episodes shared on YouTube and Instagram, fans will find a treasure of rare photos, interview clips, and candid moments captured at key stages of his life. Additionally, from November 2024 to January 2025, at Paris’s Eric Dupont gallery, the artist will showcase other talents, ones you hang on walls rather than listen to. His drawings, created in ink and sometimes enhanced with collages, are, as he admits, a direct response to his music—a medium he turns to when his writing becomes less fluid, allowing him to start afresh. A form of catharsis, in a sense.

At the same time, the remarkable Keziah will unveil a new rendition of his Future Symposium, a hybrid show with song and dance, first performed at the Centre Pompidou in 2021, drawing once again on inspiration from Fela Kuti. This story goes back to 1978, when a journalist asked Fela if he felt he was displaying his African identity enough. His response, a sharp retort typical of the icon: “We’ll see about that in a symposium, in the future.” Hence, Keziah’s desire to finally address this question—not directly, but by tracing the journey of an exiled Black musician. And without forgetting that today, the landscape, especially in Nigeria, has changed considerably.

Dream Bearer

In Keziah’s homeland, music has continuously reinvented itself, each time driven by visionary pioneers. Thus, in the early 20th century, highlife—a mix of traditional sounds, jazz, and calypso from Ghana—was followed in the 1970s by the whirlwind of local afrobeat. Led by Fela Kuti, along with Tony Allen, this new genre evolved from highlife but infused with funk and more outspoken politically, inspiring an entire generation to break free from constraints. By blending African influences with blues, funk, and primarily pop, the brilliant Mr. Jones finally removed the remaining barriers that kept his predecessors distanced from the West.

And so, the young Nigerian scene, for which Fela and later Keziah paved the way, now advances with a lightness previously unthinkable. Today, the champions of afrobeats, the leading genre of the moment, confidently deliver a fusion style designed for unrestrained celebration. It’s a vibrant blend where, alongside traditional music, hip-hop, dancehall, and R&B come together. Yet while Keziah Jones is delighted, he also notes that beyond the lightheartedness of this movement, voices from this new generation of musicians, like Wizkid and Davido, rose up against the unacceptable police violence in Nigeria in 2020. Nor would he have missed how megastar Burna Boy, a Fela sample enthusiast, frequently addresses his country’s injustices in his lyrics. “While I think it’s important for an African musician to break away from the stereotypes associated with African musicians, it’s clear to me that today’s and tomorrow’s stars will never turn a blind eye,” he observes. And he concludes gracefully, with conviction: “Music is a spiritual gift, something that raises awareness.”

TV

Andres Garrido

andres.garrido@because.tv

01.53.21.53.27

Directeur Marketing

Arnaud Nicolas

nicolas.arnaud@because.tv

01 53 21 52 73

Responsable Promotion

Daniela Soares

daniela.soares@because.tv

01.53.21.52.62

Radio généralistes

Paul Lucas

paul.lucas@because.tv

01.53.21.52.66

Project Manager

Matthieu Le Goff

matthieu.legoff@because.tv

Digital project manager

Octavie Cros

octavie.cros@because.tv

Project manager assistant

Chaima Kartobi

chaima.kartobi@because.tv